Harvey remembered: A story in three parts

A story in three parts

This week marks a five-year anniversary that most Katy-area residents would likely rather forget. It featured an uninvited, unwelcome visitor that brought with it heavy winds, extensive flooding and catastrophic property damage.

This item is available in full to subscribers.

Attention subscribers

To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, below, or purchase a new subscription.

Please log in to continue |

Harvey remembered: A story in three parts

A story in three parts

This week marks a five-year anniversary that most Katy-area residents would likely rather forget. It featured an uninvited, unwelcome visitor that brought with it heavy winds, extensive flooding and catastrophic property damage.

Although Rockport, situated 178 miles southwest of Katy, has the sad distinction of being the storm’s Ground Zero, Katy took its share of Hurricane Harvey’s force.

Remembering Harvey, and Katy’s response to it, is a story told in three parts.

Part 1: The storm

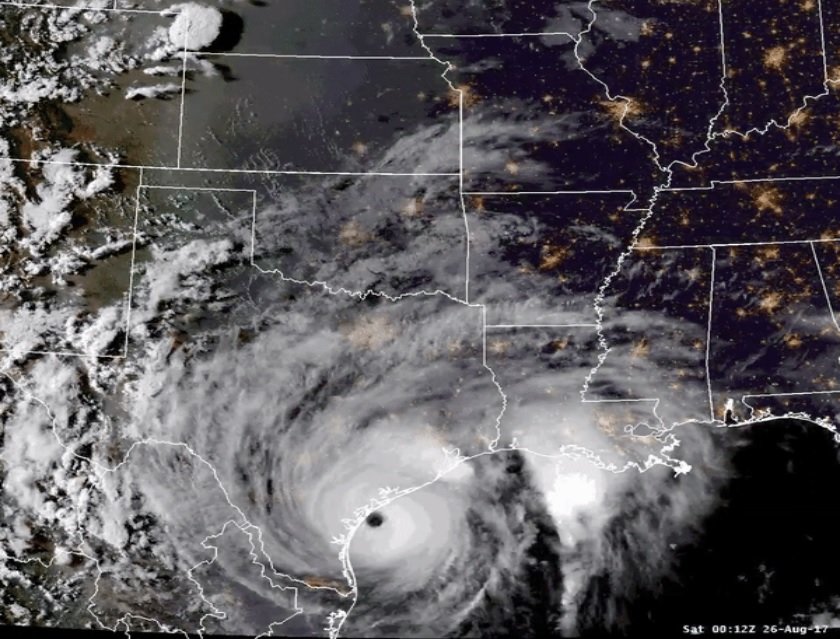

The National Weather Service said Harvey began as a tropical wave on Aug. 13, 2017, and tracked westward across the Atlantic Ocean. On Aug. 17, it became a tropical storm and moved into the Caribbean Sea, where it became disorganized.

By Aug. 23, the weather service said, Harvey had entered the Gulf of Mexico and was upgraded to a tropical depression. The storm intensified into a Category 4 hurricane.

The weather service said Harvey made landfall at about 10 p.m. Aug. 24 near Port Aransas. It moved inland, slowly moving to just north of Victoria.

Rain bands on the eastern side of the circulation of Harvey—the “dirty side” of the storm—moved into southeast Texas Aug. 25 and continued into Aug. 26. A strong rainband developed over Fort Bend and Brazoria counties during the evening hours of the Aug. 26 and spread into Harris County. Those rainbands slowed and resulted in heavy rains that caused flash flooding across much of Harris County.

On the morning of Aug. 27, the weather service said, more rain bands developed and produced excessive rainfall. As the center of Harvey slowly moved east-southeast and back offshore, heavy rainfall continued to spread through much of Aug. 29-30. The situation became worse.

Harvey maintained tropical storm intensity the entire time while inland over the Texas coastal bend and southeast Texas. After moving offshore, Harvey made a third landfall just west of Cameron, La., the weather service said.

Part 2: The damage

Floodwaters came from north of the city, where the Pine Forest subdivision—bordered by Morton Road on the north, the Magnolia Ditch on the south, Cane Island Branch on the west, and Avenue D on the east—became what then-Mayor Chuck Brawner called the “bulls-eye” of flooding in the city.

But other parts of the city flooded, too. Katy’s City Hall building, opened in 2016, sustained extensive flooding damage. The wood paneling in the council chamber had to be removed, along with so much else, for remediation and restoration. Brawner and the council held meetings in a room next to the council chamber at first. Later, meetings returned to the chamber, with plastic covering over the walls.

The Katy Independent School District’s Education Support Complex, along with the Merrell Center, 6301 S. Stadium Dr., both sustained flooding damage.

But the floodwaters came from south of the city from the Barker Reservoir, with the Canyon Gate subdivision sustaining extensive damage.

Creech Elementary School, 5905 S. Mason Rd., was the worst hit of the Katy ISD schools. The damage was so catastrophic that the school, which opened in 2000, had to be closed for remediation and restoration.

Meanwhile, the students needed a place to attend school. George Scott, who was a school trustee during Harvey, said then-Superintendent Lance Hindt learned that the University of Houston was selling its Cinco Ranch building, 4242 S. Mason Rd. Hindt contacted the university, Scott said, and arranged to have the district buy the building. That building sits 1.2 miles away from the Creech campus.

District and school staff worked to convert the building into a suitable elementary school campus, and students attended their classes in what became known as Creech University.

Part 3: The recovery

Other Katy ISD schools became shelters for displaced residents. Cinco Ranch High School, 23440 Cinco Ranch Blvd., and Morton Ranch High School, 21000 Franz Road, became makeshift shelters for residents.

The Katy High School parking lot, 6331 Highway Blvd., became a command center for Texas National Guard rescue operations.

Like so many area homes, churches and businesses that sustained flood damage, schools were remediated and renovated. Creech Elementary, in August 2017, held an open house for students and parents, staff and alumni. The project cost $3.5 million for remediation and $5.5 million for reconstruction.

After the school sustained the damage, the district removed the debris and flood-damaged walls. It reconfigured the entrance way to a set of bathrooms. The hallway leading to those restrooms was removed so teachers and staff could better monitor who was coming and going. The restrooms proved the most challenging renovation because of the necessary pipe cutting and plumbing relocation.

Classrooms were redesigned to include a window that enables teachers and students to see into a hallway, and the windows enable people in the hallway to see inside the classrooms. Whiteboards were installed on a track that enables teachers to slide it in front of the window, thus blocking the ability to see into the classroom, if a safety concern develops.

Katy city officials worked to mitigate and repair the damage. In May 2018, less than a year after Harvey, Katy city voters approved a $19.25 million bond that dealt with flood prevention issues. The bond comprised three propositions.

- The first proposition, for $4.25 million, was for street work to elevate the 1st Street bridge and Katy Hockley Road (Avenue D). Breaking down the proposition further, $1.25 million was for elevating the bridge, and $3 million was for Katy Hockley Road.

- The second proposition, for $10.25 million, was for drainage projects for the Fortuna and Pine Forest subdivisions. Phase II of this project was for a detention pond at Pitts Road.

- The third proposition, for $5 million, was for expansion of the city’s sewer plant.

The city in September 2017 purchased a new truck to help move people should the situation arise again.

The truck, which has a 2.5-ton capacity, is a light medium tactical vehicle (LMTV), built at the BAE Systems plant in Sealy. According to Military.com, this type of vehicle has been used for general and ammunition resupply, engineering support, and maintenance and recovery missions.

At the time, officials said Katy got a good deal on the truck, paying a four-figure price for a truck that sells for six figures.

The council has continued to support public works projects intended to reduce or mitigate flooding. In April, the city launched a website, the abbreviated URL for which is bit.ly/3IWA9TiXX, that enables citizens to learn the latest on city public works projects.

Katy-area residents can also stay informed through an automated alert notification system set up by the city. Enrollment is free and can be done through the city’s website, the abbreviated URL for which is bit.ly/3sTqg3u.

Churches, citizens and nonprofit groups such as Katy Christian Ministries and Katy Responds, continue to help those in need as, in some cases, recovery efforts continue.

The big trucks aren’t limited to local first responders, either. One couple, Aaron and Rosemary Jackson, founded ARHTX Army, a nonprofit dedicated to educating people about hurricane preparedness.

Having their own LMTV M1078 Deuce-and-a-half truck—called “General Max”—to help spread hurricane preparedness tips helps. The Jacksons said they named the truck in honor of General Maximus Decimus Meridius from the movie The Gladiator. Meridius never gave up and aided others with their survival.

Good advice for all Katy-area residents as they remember Harvey five years later.

Keywords

City of Katy, Katy ISD, Katy Independent School District, Hurricane Harvey